What is Episodic weakness and collapse?

Essentially, ‘episodic weakness and collapse’ refers to involuntary falling over! Dogs are more commonly presented to veterinary surgeons with this problem than cats. Syncope (pronounced sin-coh-pea) is the technical term for fainting when the patient temporarily loses consciousness. Collapse, such as fainting, may be completely benign and require no treatment. However, in some circumstances it is due to a life-threatening situation that requires a specific treatment.

We need to be sure we aren’t just dealing with an isolated incident of exhaustion! However, don’t take a chance. You must call your vet if you are concerned.

Remember these conditions are both Involuntary (the patient has no control over them) and intermittent or ‘episodic’ and the patient may be completely normal between bouts. There are no seizures or fits as we see in Epilepsy. Also, before starting our investigations, we need to be as sure as possible that involuntary collapse is truly occurring. If a dog is choosing to lie down, for instance because of tiredness or heat exhaustion, or because of feeling faint after pulling hard on the lead this is not collapse.

What causes episodes of weakness, collapse or fainting?

The causes are many and varied and can involve:

- The airways

- The heart and blood vessels

- The nervous system – brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves

- The muscles, bones and joints

- A malfunction of one or more chemical processes occurring in one of a number of body organs (these are usually referred to as ‘Metabolic’ causes).

To further complicate matters there are plenty of potential causes of collapse within each of these broad categories. So, what might seem to be a relatively ‘simple’ clinical presentation can turn into the proverbial search for a needle in a haystack when it comes to finding out the cause of the problem.

Investigations can therefore be costly, frustrating and extremely time consuming for all concerned. For example, it is quite common for blood samples to be sent to more than one specialist laboratory and some of these may be outside the UK. Finally getting all the results together can take several days or even weeks. It can be a trial of patience waiting for such tests but it is better to wait for accurate results than to choose a more rapid but less helpful alternative.

How can pet owners and carers help in getting to a diagnosis?

You can help a great deal by giving an accurate account of events leading up to the collapse

Getting to a diagnosis is clearly very important so we know how to treat effectively. You can help your vet a lot in this regard! It is often very helpful if video footage of the events occurring can be provided as sometimes this may show important information which to the untrained eye may not be obvious. Your vet may well not see the event you are concerned about as by their very nature these are intermittent events.

It is very helpful to know the following:

- What a pet is doing just before he or she collapses

- What he or she does during the collapse

- What he or she does after the collapse

Your vet will then want to perform a thorough clinical examination. Ideally, the information you provide and the results of your vet’s examination will give diagnostic ‘clues’ as to which direction in which to look first. If these findings make one particular cause of collapse more likely than others then this gives a far better chance of determining the cause. A problem arises where signs are vague and do not allow us to ‘home in’ on a particular group of possibilities. In these circumstances unfortunately investigation needs to be very broad-based and we would start by evaluating for the most common causes of collapse.

How is collapse investigated?

There is no single test that will evaluate the patient for all causes of collapse. Tests are picked on an individual basis according to how valuable the clinician expects the test to be in a particular case. This is why the intial information and history is so important because it will help the clinician to be more specific with the tests performed and therefore more likely to discover the cause.

A dog wearing a special vest which contains a 24-hour ECG monitor called a Holter monitor.

Each case is different but investigations will often involve

1. Blood tests to look for metabolic causes

2. Assessment of the heart by an electrocardiogram (ECG), an echocardiogram (heart ultrasound) and chest x-rays. In some patients where an intermittent electrical abnormality is suspected, the patient will be fitted with a device to perform an ECG for 24 hours in an effort to ‘catch’ the irregular heart rhythm. This special ECG device is called a Holter monitor and it is connected to sticky pads which adhere gently to the skin to allow the rhythm of the heart to be recorded for extended periods of time and even at home.

If these tests are normal then further testing depending on the remaining clinical possibilities is indicated. Sometimes further tests may be advised straight away or in some instances it may be worth performing these after a delay both to make sure that the problem is persisting and also to allow some time for further ‘clues’ pointing to a particular diagnosis to develop.

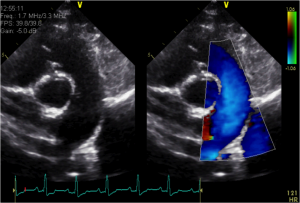

An ultrasound examination of the heart (echocardiogram). The two images show the same area of the heart with the ‘black’ areas being blood within the chambers and blood vessels. In the image on the right, the vivid ‘blue’ is the direction and speed of blood flow being superimposed on one of the vessels by a technique called Colour-Flow Doppler ultrasound. This heart was normal.

Is a specific diagnosis always found?

In some instances, despite lengthy and thorough investigation, no cause of the collapse is found. The same is also true in human medicine. Sometimes this may be because the cause is either benign or occurring so rarely that the cause is not caught ‘in the act’. Other causes of collapse may remain undiagnosed because some potential causes are simply not possible to evaluate in dogs and cats, particularly tests that in humans would require a period of voluntary bed rest – clearly this is not possible to achieve in a dog or cat.

How is Episodic weakness and collapse treated?

This completely depends on identifying the cause. We will discuss some of the causes of episodic weakness and collapse in subsequent articles.

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.