Parasitism is a non-mutual relationship between two or more species, where one species, the ‘parasite’, lives on or in and benefits from its ‘host’ (at the expense of the host).

What is a ‘parasite’?

Traditionally the word ‘parasite’ refers mainly to organisms visible to the naked eye (so called ‘macroparasites’) but is now used also for smaller organisms, such as viruses and bacteria (‘microparasites’).

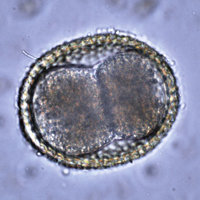

A roundworm egg viewed under a microscope

Many parasites do not directly kill their host and are often much smaller than it, living in or on their host for an extended period of time and reproducing at a faster rate. For example, a single adult Toxocara canis (a roundworm) can produce as many as 85,000 eggs per day.

Although often not killing their host, they can directly cause illness, or transmit other infectious diseases. Some parasites can only live on/in one host species, whereas others are less fussy and can live on/in several (known as their ‘host range’), especially if they are similar mammals (e.g. humans and dogs). For this reason, some animal parasites can also affect humans (so called ‘zoonotic parasites’ / ‘zoonoses’).

Which parasites affect dogs and cats?

The most common UK dog and cat parasites externally are fleas and ticks, and internally, coccidia and worms. If your pet travels with you though, say to Europe, other ‘non UK’ parasites can become very important, such as Leishmania or heartworm.

What is the life cycle of a parasite?

Their life cycles are very variable, maturing from some sort of egg or cyst, to larvae or intermediate stage(s), and finally to an adult form (which can reproduce to produce more eggs/cysts and complete the cycle).

These life cycles often involve only one host species, a ‘definitive host’ (within which they can reproduce, such as dogs and cats), whilst others use an ‘intermediate’ or carrier host (‘paratenic host’) in between (such as snails, mosquitoes and sandflies). Sometimes the host can be infected, but not as part of the parasite’s life cycle (these are ‘accidental’ or ‘dead end’ hosts, such as humans).

Endoparasites live inside their hosts, whereas ectoparasites live on the surface or skin of their hosts. An example life cycle is given for roundworms below. However, some parasites have much more complex and sometimes alternate life cycles that vary with the environmental temperature and conditions.

Roundworm life cycle in kittens and puppies

- Ingested roundworm eggs hatch in the guts, and the hatched larvae migrate through the body tissues.

- Eventually they reach the lungs, where they make their way up the windpipe, are coughed up and then swallowed.

- Once swallowed this time, the larvae then become adult roundworms in the intestines.

- These adults produce numerous eggs, which are passed in the faeces.

- The eggs only become infective to other dogs after a week or two in the environment.

Roundworm life cycle in adult dogs

In adult dogs, especially females, the situation can be different to that in kittens and puppies.

- After ingestion, the larvae migrate through the gut wall and into other tissues, where they enter a dormant (‘sleeping’) state.

- In a pregnant female, the larvae become active again, possibly crossing the placenta directly into the pups and/or are secreted in the milk after birth.

- They can also produce an active adult roundworm infection, again in the mother’s intestines, then shedding numerous eggs that can also infect the puppies.

- Toxocara canis (a roundworm) can therefore very readily infect puppies in large numbers within a few weeks of birth.

Other noteworthy life cycle variations between different parasites are:

- Rodents (e.g. mice, rats, voles) can also carry larvae and the dog or cat can then become infected by eating an affected rodent.

- Hookworms can infect adult animals, entering through intact skin, especially on the feet that contact faecal material, as well as through wounds.

- Snails act as the intermediate host for lungworm, Angiostrongylus vasorum (aka. ‘french heartworm’).

Fleas can also act as carriers or ‘vectors’ for tapeworms

Parasites can also act as vectors, such as fleas for a tapeworm – transmitting other infectious diseases which can be more significant and life threatening than the vector parasite itself. Ticks for example can transmit Babesia (another parasite) which damages the animal’s red blood cells.

Therefore, both the parasite and transmitted disease may need to be treated.

How common are these parasites?

Much of the information is unknown for many parasites, or may only be available from old studies that can be over twenty years old, so may no longer be appropriate given changes in climate and temperature. The risk for each animal can then be very variable, from almost non-existent (a high rise, indoor cat) to very high (puppy on a farm with many other dogs and animals).

How do we know if an animal has parasites?

The honest answer is we often don’t, as most single tests only provide information on particular parts of a parasite’s life cycle at that one time. Repeated tests may then be required to confirm that an animal has an infection. Otherwise, the animal may show signs consistent with infection and if no anti-parasitic therapy has been given recently to prevent infestation, treatment will be given to eliminate the possible parasites. When tests are performed, they may include the following…

Tests for endoparasites

Adult worms are very variably sized (ranging from a few millimeters to nearly a metre!), white/cream to pale brown in colour, round string or spaghetti- like objects. Tapeworms form very variable chain lengths of similar coloured square/rectangular segments. Adults can be visible to the naked eye in faeces or vomit, sometimes individually stuck to an animal’s fur, especially around the anus/bottom, such as tapeworm segments. This though is uncommon.

Faecal samples are typically taken, often on one or more occasions. A small representative part of the faeces is then added to a liquid solution and further concentrated via spinning in a centrifuge, to allow the eggs and larvae to be seen more easily under the microscope. Sometimes smaller bits of the parasite can be dissolved out of the faeces and amplified using coloured test kits.

Tests for ectoparasites

These may be seen with the naked eye on the skin surface (such as lice and ticks), others are too small to see and/or may be living within the skin. Your vet will then perform skin scrapes and or hair plucks, using forceps/tweezers, blunted scalpel blades and/or swabs and sellotape. The material is then put on a slide and examined under the microscope to see the mites/parasites.

Blood samples can also be taken, these looking for very small bits of the larvae or adults in the circulation, or possibly the animal’s antibody/immune response to the parasite.

However, even if the parasites are not seen in that sample or no antibodies are found, whether it is skin, blood or faeces, this does not necessarily mean the animal does not have that infection. Repeat or serial samples can be required, especially if the infection is very recent. Otherwise, extra tests such as blood samples can be taken to try to identify longer standing infections.

In the second part of this article on Pet Parasites, we will look at how animals with parasites can be treated, and how to prevent your pets from getting parasites in the first place!

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.

The Veterinary Expert| Pet Health

The veterinary expert provides information about important conditions of dogs and cats such as arthrits, hip dysplasia, cruciate disease, diabetes, epilepsy and fits.